Overview of Pudendal Neuralgia

Pudendal neuralgia is a condition that affects the pudendal nerve, which transmits sensory information from the perineal region to the brain. People who experience pudendal neuralgia often describe it as a burning, shooting, or stabbing pain in the pelvic region.

-

Diagnosis of Pudendal Neuralgia

To diagnose pudendal neuralgia, healthcare professionals may utilize nerve conduction studies. These studies evaluate the electrical signals transmitted along the pudendal nerve, helping to identify any abnormalities or impairments. This diagnostic tool can provide valuable insights into the functioning of the pudendal nerve and assist in formulating a treatment plan.

-

Causes of Pudendal Neuralgia

One of the primary causes of pudendal neuralgia is pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome. This occurs when the pudendal nerve becomes compressed or trapped, leading to pain and discomfort in the pelvic area. Advanced practitioners, such as physical therapists specializing in pelvic health, can work alongside healthcare professionals to address this condition comprehensively.

-

Treatment Options for Pudendal Neuralgia

Various treatment options are available for managing pudendal nerve pain. Pudendal neuromodulation, for instance, has shown promise in providing relief to individuals experiencing pudendal neuralgia. This technique involves implanted devices delivering electrical impulses to the pudendal nerve, helping to modify and alleviate pain signals.

-

Impact on Sexual Health

Pudendal neuropathy, another term often used to describe pudendal neuralgia, can have a significant impact on sexual health and function. Many individuals with this condition may experience sexual dysfunction, such as pain during intercourse or diminished sensation in the genital area.

Addressing sexual health concerns should be approached holistically, with input from healthcare professionals specializing in both pain management and sexual health.

-

Perineal Pain and Its Management

Perineal pain is a common symptom associated with pudendal neuralgia, and it can be highly debilitating. This type of pain is often described as occurring in the area between the anus and genitals. Understanding the neuropathic nature of this pain is crucial, as it helps guide treatment strategies and ensures that appropriate interventions are employed to alleviate discomfort effectively.

-

Understanding Entrapment Syndrome

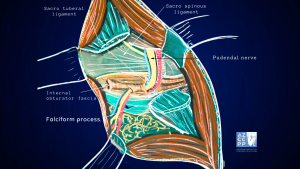

Addressing pudendal neuralgia requires a comprehensive understanding of entrapment syndrome, as it plays a significant role in the development and progression of the condition. For example, the sacrospinous ligament has been named as a place where nerves can get pinched, leading to damage to the pudendal nerves and pain.

This knowledge allows for more targeted approaches to treatment and potential surgical decompression options for those who do not respond adequately to conservative management.

-

Educating Individuals About Pudendal Neuralgia

By educating individuals about pudendal neuralgia and its symptoms, we contribute to a greater understanding of this condition. Health encyclopedias and informational resources are invaluable tools in disseminating accurate and helpful information to those seeking knowledge about their condition. Empowering individuals with knowledge enables them to make informed decisions regarding their healthcare and seek appropriate treatment and support.

- Comprehensive

Care and Management

Pudendal neuralgia is a complex condition that can significantly impact pelvic health and sexual function. With the guidance of healthcare professionals and advanced practitioners and the use of diagnostic tools like nerve conduction studies, we can better understand and effectively manage pudendal nerve pain.

By exploring treatment options such as pudendal neuromodulation and addressing related symptoms like sexual dysfunction, we can strive towards improving the quality of life for individuals with pudendal neuralgia.

Pudendal Neuralgia: Relatively Unknown Cause of Severe Pelvic Pain

In my practice, I define it as pain located in the area of innervation of the pudendal nerve. Pudendal nerve entrapment is an impingement of the pudendal nerve due to scar tissue, surgical supplies, or mesh. Pudendal nerve entrapment is, therefore, one of the causes of pudendal neuralgia.

However, other causes, such as inflammation, spasms of the surrounding muscles, or other nerve diseases, may also be a reason for pain.

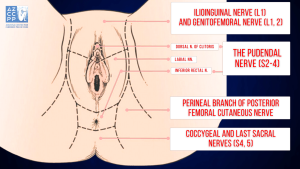

Innervation of the Perineum

Innervation of the Perineum

Pudendal nerve entrapment is almost always caused by a traumatic event in the pelvis. This may include pelvic surgery (with or without mesh), difficult childbirth, athletic injuries, falls, and other accidents. A repetitive injury, such as bicycle seat pressure on the pelvic floor, may also lead to pudendal nerve entrapment (cyclist syndrome).

Diagnosis of pudendal nerve entrapment is not easy and relies heavily on taking a detailed history. Pain is located in the vagina, vulva, clitoris, perineum, and rectum, and it may involve one or all of those areas. Pain is more severe when sitting than when standing or lying down, and sitting on the toilet is generally better than sitting on a chair.

Most of the patients with real nerve pain injuries have pain on one side only, or one side is significantly more painful than the other. Chronic Pelvic Pain is generally more severe with urination, bowel movements, and intercourse. Some patients may also have difficulty emptying their bladder (hesitancy) and bowel (constipation).

One of the most debilitating symptoms of pudendal nerve entrapment is a sensation of continuous sexual arousal (persistent genital arousal disorder, or PGAD). Patients often reduce this sensation through masturbation, which only provides temporary relief.

Nantes Criteria

My mentor, Professor Roger Robert, a pioneer in the treatment of pudendal nerve entrapment, has developed Nantes criteria that greatly assist in diagnosing this condition. Studies have shown that patients who more closely meet the criteria have better outcomes from the surgical decompression of the nerve.

Inclusion Criteria |

|

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Complementary Criteria |

|

Associated Signs |

|

Inferior Rectal Nerve |

Cutaneous Branch of the Obturator Nerve |

Lateral Cutaneous Branch of Iliohypogastric Nerve |

Femoral Branch of Genitofemoral Nerve |

Posterior Femoral Cutaneous Nerve |

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve |

Iliohypogastric Nerve |

Clitoral/Perineal Nerves |

Femoral Nerve |

Genital Branch of Genitofemoral Nerve |

Other Nerves Innervating the Pelvis |

Pain in pudendal nerve entrapment is of a neuropathic nature, which means that patients feel burning, tingling, and numbing sensations (paresthesia). Some patients have the sensation of a foreign body located in the rectum or vagina (allotriesthesia) and may describe it as a “red hot poker” in the rectum.

Some patients do not experience any chronic pain but have complete or partial numbness in the area of innervation of the pudendal nerve.

Extra tests, such as magnetic resonance neurography (MRN), pudendal nerve motor terminal latency (PNMTL), another electrophysiologic test, or sensory threshold testing, can usually not determine if someone has pudendal nerve entrapment.

An important part of the Nantes criteria is a CT-guided pudendal nerve block, which is used to find and treat pudendal nerve entrapment. If pain doesn’t go away right away after a CT-guided pudendal nerve block, it’s likely that the pudendal nerve is not the source of the pain.

Conservative Treatments of Pudendal Neuralgia

Pudendal neuralgia is a challenging condition that can cause significant discomfort and impact daily life. Fortunately, there are various conservative treatments available to help manage the symptoms and improve quality of life. This guide provides an overview of effective non-invasive methods that can be employed to alleviate pain and protect the pudendal nerve.

-

Avoidance of Additional Injury

Patients must immediately cease activities that lead to nerve injury. For example, if pudendal neuralgia was caused by riding a bicycle, the patient should stop cycling immediately. Avoiding such activities is crucial to prevent further damage to the nerve. However, this approach may not be feasible in cases where the patient develops pudendal neuralgia as a result of surgery or childbirth.

-

Nerve Protection

Protecting the pudendal nerve is vital for managing pain and preventing further injury. This can be achieved by using specialized sitting cushions that relieve pressure on the pelvic area, zero-gravity chairs that distribute weight evenly, or kneeling chairs that reduce strain on the lower back and pelvis. These tools help minimize discomfort and protect the nerve from additional stress.

-

Medications

Various medications can be used to manage the pain associated with pudendal neuralgia. Oral medications, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and pain relievers, can provide relief. Additionally, vaginal or rectal suppositories can deliver medication directly to the affected area, offering targeted pain relief and reducing inflammation.

-

Pelvic Floor Therapy

Appropriate pelvic floor physical therapy can play a significant role in managing pudendal neuralgia. This therapy aims to minimize pelvic floor muscle spasms, which can contribute to nerve pain. Physical therapists specializing in pelvic health can develop personalized exercise and stretching routines to improve muscle function and reduce tension in the pelvic region.

-

Botulinum Toxin A Injections

Botulinum toxin Injections, commonly known as Botox, can be administered to the pelvic floor muscles to alleviate muscle spasms. By relaxing the muscles, these injections can reduce pressure on the pudendal nerve and provide relief from pain. This treatment option is often used in conjunction with other conservative therapies for maximum effectiveness.

-

Pudendal Nerve Blocks

Pudendal nerve blocks involve the injection of an anesthetic and/or steroid medication near the pudendal nerve to reduce pain and inflammation. These injections can be guided by CT or ultrasound imaging, or they can be performed unguided transvaginally. The goal is to restrict the nerve as it enters the lesser sciatic foramen, 1 cm inferior and medial to the sacrospinous ligament-ischial spine attachment. This procedure can provide temporary relief from pain and is often used as a diagnostic tool to confirm the source of pain.

-

Pudendal Nerve Injections

Injections containing amniotic fluid and a liquified amniotic membrane can be used to treat pudendal neuralgia. These injections provide anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties, promoting healing of the nerve. The use of amniotic products can help reduce pain and improve nerve function over time.

-

Ablation Procedures

Pulsed radiofrequency ablation (pRFA) and cryoablation are minimally invasive procedures that can be used to treat pudendal neuralgia. pRFA uses electrical pulses to disrupt pain signals and reduce nerve sensitivity, while cryoablation involves freezing the nerve to block pain transmission. Both techniques aim to provide long-lasting pain relief and improve the patient’s quality of life.

-

Nerve Stimulators and Spinal Cord Stimulators

Implantable devices, such as nerve stimulators and spinal cord stimulators, can be used to manage chronic pain in pudendal neuralgia. These devices deliver electrical impulses to the pudendal nerve or spinal cord, disrupting pain signals and providing relief. They are typically considered when other conservative treatments have not been effective.

-

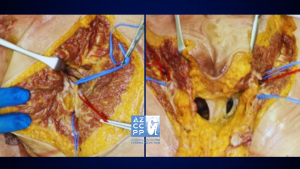

Surgical Decompression of the Nerve

Surgical decompression of the pudendal nerve can be performed using several different approaches, including transgluteal, transischorectal, transperineal, and laparoscopic/robotic techniques. The goal of the surgery is to free the nerve from any entrapment or compression, thereby reducing pain and improving function. This option is usually considered when conservative treatments have failed to provide adequate relief.

Professor Roger Robert first described the transgluteal approach in Nantes, France, after which I significantly modified it. This approach offers, by far, the best access to the pudendal nerve, therefore allowing for the most complete decompression.

One of the technique’s earlier drawbacks was cutting the sacrotuberous ligament, which, in some cases, could lead to pelvic instability. However, the risk of that instability was eliminated when I began repairing the sacrotuberous ligament.

Cutting that ligament frees the nerve from scar tissue or surgical materials and allows access to the nerve. However, the sacrotuberous ligament should be fixed after nerve decompression is complete.

Other Modifications I Have Introduced to the Pudendal Neurolysis Surgery

In order to enhance the outcomes of pudendal neurolysis surgery, I have introduced several modifications to the procedure. These modifications are designed to improve visualization, ensure nerve integrity, manage pain more effectively, and promote better healing. Below are the key changes I have implemented:

-

Use of Surgical Microscope

The use of a surgical microscope allows for better visualization of the nerve and the surrounding structures. This enhanced visualization is crucial for precise dissection and identification of the pudendal nerve, reducing the risk of accidental damage to the nerve and improving surgical outcomes.

-

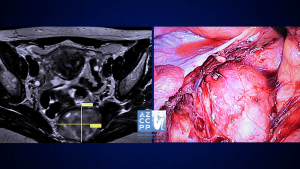

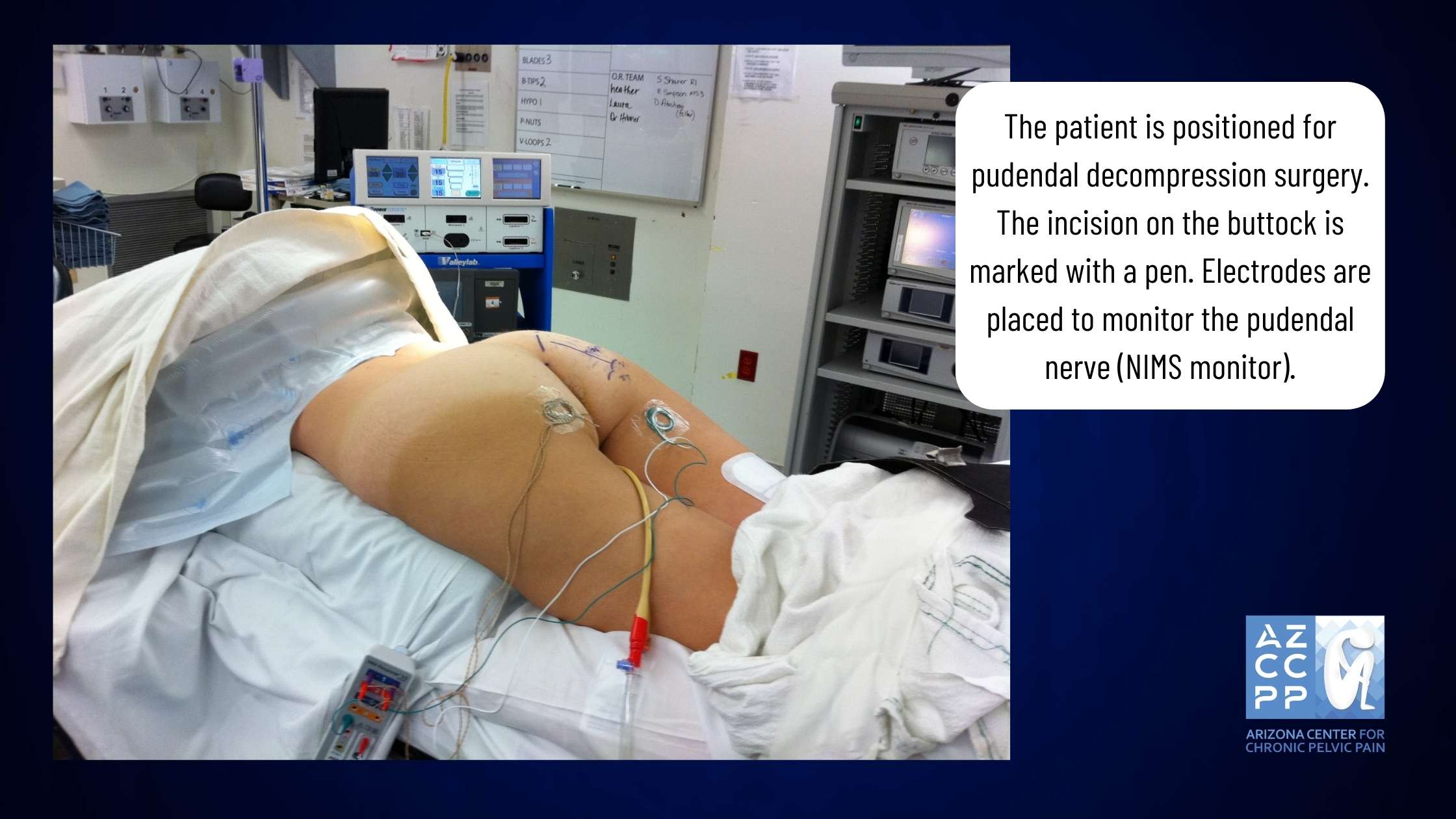

Nerve Integrity Monitoring System (NIMS Monitor)

The Nerve Integrity Monitoring System (NIMS monitor) can help identify the pudendal nerve. This system is especially helpful in cases where the nerve is significantly scarred or in repeat surgeries where the anatomy may be altered. By providing real-time feedback on the nerve’s function, the NIMS monitor helps ensure that the nerve is properly identified and preserved during the procedure.

-

Pain Pump

The use of a pain pump that delivers a local anesthetic to the nerve for about seven days after surgery can significantly decrease pain levels. This continuous infusion of anesthetic helps to reverse central sensitization, which is the memory of pain in the brain. By reducing pain and central sensitization, patients may experience a faster recovery and resolution of pain after surgery.

-

Nerve Wrapping with Adhesion Prevention Barrier

Nerve wrapping with an adhesion prevention barrier decreases the risk of scarring or re-scarring of the nerve after surgery. Several years ago, I switched from regular nerve wraps to wrapping the nerve with an amniotic membrane product.

In addition to anti-adhesion (anti-scarring) properties, the amniotic membrane contains nerve growth factors that promote nerve healing. It also may have the ability to attract your own body’s stem cells close to the nerve, which further helps with nerve regeneration.

-

Use of Suction Dressings

Using suction dressings after closing the skin helps minimize the risk of wound infection. These dressings create a vacuum effect that promotes better healing by reducing the accumulation of fluids and decreasing the chances of bacterial growth in the surgical site.

A microscope is used for transgluteal pudendal surgery, with a NIMS monitor for monitoring the nerve during surgery.

A microscope is used for transgluteal pudendal surgery, with a NIMS monitor for monitoring the nerve during surgery.

Laparoscopic/robotic procedures are less invasive, but they do not offer as good access to Alcock’s canal as transgluteal procedures do. It may be effective in cases where the nerve compression is limited to a small area, but the location of the compression may be difficult to determine prior to surgery.

In my practice, I perform both transgluteal and robotic nerve decompression procedures, but I believe that since the transgluteal technique offers better access and allows for decompression of the larger part of the pudendal nerve, it should be a preferred approach.

Even though the recovery time is longer compared to the laparoscopic procedure, the benefits of more complete nerve decompression are very important when considering the choice of surgery.

Overall, the surgery results show that most patients have significantly decreased pain and benefit from pudendal nerve decompression procedures.

If you or someone you know experiences pain from sitting in the clitoris, vulva, penis, scrotum, perineum, or rectum, call 480-599-9682 or email [email protected] to learn more about available treatments.

View of the pudendal nerve through the microscope (nerve in the blue rubber band—vessel loop)

View of the pudendal nerve through the microscope (nerve in the blue rubber band—vessel loop)

What to Expect Before and After Transgluteal Nerve Decompression Surgery

Transgluteal nerve decompression surgery can be a crucial step in managing the debilitating pain caused by Pudendal Neuralgia. Understanding what to expect before and after surgery is essential for a smooth and successful recovery process. Here’s a comprehensive guide to help you navigate the journey:

-

Pre-Surgery Non-Invasive Methods

Before surgery, Dr. Hibner and his team will use noninvasive methods, such as physical therapy, suppositories, oral medications, nerve ablations, and amniotic fluid or membrane product injections, to help manage your pain.

-

Collaborative Decision for Surgery

The decision to undergo surgery is made collaboratively between you and Dr. Hibner, considering your medical history, exam results, radiology findings, and any additional testing. Surgery is considered when all conservative treatments have failed.

-

Surgical Approach and Pre-Operative Instructions

Dr. Hibner’s preferred method is transgluteal pudendal nerve decompression to free the nerve from scar tissue. In some cases, a robotic or alternative approach may be chosen. Follow all pre-operative instructions provided during your visit.

-

Surgery Positioning and Incision

During the surgery, you will be positioned prone (on your abdomen), and an incision will be made on the operated side of your buttock, measuring 2 to 4 inches.

-

Recovery Room Experience

After surgery, you will wake up in the recovery area with a bladder catheter, a pain pump delivering local anesthetic to your nerve, and a negative pressure dressing on the incision. You will receive a bag for the pain pump and a suction device for the dressing.

-

Post-Surgery Pain Management

You should feel numbness in the pudendal nerve area (where the pain was before surgery), but the buttock incision will be tender. The pain pump medication targets nerve pain and does not reach the muscles or skin of the buttock.

-

Hospital Stay and Activity Recommendations

Most patients spend one night in the hospital, with rare cases requiring a two-night stay. Be active and try to walk with support the day after surgery to prevent muscle loss and reduce the risk of nerve scarring. Avoid pulling the pain pump while moving.

-

Discharge and Home Care Instructions

You will be discharged with pain medications, instructions on using the pain pump, and a negative pressure dressing. You may need to return to the clinic for dressing and pain pump removal, or you may be instructed on how to do it yourself. Pain may increase temporarily after the pain pump is removed.

-

Showering and Travel Guidelines

You can shower two days after surgery but should avoid getting the incision area wet. Use a large garbage bag to protect the area during showers. Most patients can travel within 5-7 days after surgery, but a longer stay is recommended before returning home.

-

Activity and Physical Therapy

Resume activities gradually, avoiding actions that significantly increase pain. Avoid sitting, and if surgery was done on one side, sit only on the opposite buttock. Do not flex your hip(s) over 90 degrees to protect the repaired sacrotuberous ligament, which takes about six months to heal. Pelvic floor physical therapy should resume approximately six weeks after surgery.

-

Pain Improvement and Follow-Up

It may take 3–4 months to start feeling pain improvement. Continue taking all medications until advised otherwise, and reduce narcotic pain medications as instructed. Maximum healing may take 18 to 24 months, with most patients experiencing less or no pain after two years. If pain persists, additional solutions will be explored.

Outcomes

The outcomes of this procedure depend on the causes of nerve compression, the degree to which the nerve was compressed, and how much time elapsed between the injury and surgery. Unfortunately, the degree of nerve damage is difficult to assess before surgery.

From my extensive experience of doing hundreds of pudendal decompression surgeries, approximately two-thirds (66%) of patients benefit from this procedure. This number includes all the patients, even those with severe nerve injuries. That means that patients with less severe nerve injuries may benefit from the procedure even more.

A Little History

The book “The Change of Life in Health and Disease,” published in Philadelphia in 1871, established pudendal neuralgia as a medical condition. Knowledge of pudendal neuralgia was almost lost until the late 1980s.

French neurologist Dr. Gerard Amarenco reported on a series of patients with “syndrome du cyclist,” the cyclist syndrome, which occurs when a pudendal nerve is compressed between a narrow bicycle seat and the medial surface of ischial tuberosity (sitz bone).

Dr. Ahmed Shafik, an Egyptian surgeon, first described how to surgically decompress the pudendal nerve using the transperineal technique (an incision around the anus) in 1992. Soon after, my mentor, Professor Roger Robert from Nantes, France, described transgluteal pudendal neurolysis—decompression of the pudendal nerve with an approach through the buttock.

Professor Robert is not only an outstanding neurosurgeon but also an anatomist, and this unique combination allowed him to develop a whole new procedure for pudendal nerve decompression.

I graduated from my fellowship in gynecologic surgery at the Mayo Clinic in 2003 and opened a pelvic pain practice in Phoenix in 2004. I started seeing patients with pelvic pain whose condition I was unable to explain using any known diseases.

So, in early 2005, I googled the symptoms: perineal/vaginal burning pain with sitting. Several medical articles showed up, but most of them had one common name as one of the authors: Roger Robert. I then wrote to Professor Robert in Nantes, France, asking if I could come and learn from him.

In the summer of 2005, I traveled to Nantes and worked with Professor Robert for almost 3 weeks, assisting him with numerous surgeries and seeing many patients in the office with him.

I also worked with the wonderful Dr. Jean Jacques Labat, a neurologist who assisted Professor Robert with diagnosing and treating patients before surgery, and with the amazing radiologist Dr. Thibault Riant, who taught me how to perform CT-guided pudendal nerve blocks.

When I returned to Phoenix, I started seeing more and more patients with pudendal neuralgia and pudendal nerve compression, and I performed my first transgluteal pudendal nerve decompression in the fall of 2005.

The patient developed pudendal neuralgia after the removal of Bartholin’s gland. She did well after surgery, and soon, many more patients followed. I started modifying the original method that my great mentor, Professor Robert, had created from the very first surgery. The first modification was the repair of the transected sacrotuberous ligament.

There was a concern that leaving this ligament unrepaired may cause instability in the sacroiliac joint. So, from the very first patient, I would repair the sacrotuberous ligament the same way that an orthopedic surgeon repairs a ligament in the knee.

Next, I incorporated the use of a neurosurgical microscope into the procedure. This allowed for significantly improved precision.

The next modification was the use of an On-Q pain pump placed next to the nerve towards the end of surgery to provide postoperative analgesia and decrease central sensitization (memory of pain in the brain). In the third change, NIMS (nerve integrity monitoring system) was added so that the nerve could be found even when there was a lot of scarring.

The next modification was the use of nerve wrap to prevent the reoccurrence of adhesions. Initially, I was using a collagen nerve conduit, but a few years ago I switched to an amniotic membrane, which, in addition to preventing adhesions, also contains factors/chemicals promoting nerve healing.

The last major modification was the method by which I cut the sacrotuberous ligament. Cutting it in a Z fashion allows me better access to the nerve and facilitates the repair at the end of surgery.

Up to today, I have done several hundred of those procedures, most likely more than any other provider, with the exception of my amazing mentor, Professor Roger Robert.

For More Information, Visit:

https://www.glowm.com/section_view/heading/pudendal-neuralgia/item/691

Drawing of the steps of transgluteal pudendal neurolysis by Professor Roger Robert

Drawing of the steps of transgluteal pudendal neurolysis by Professor Roger Robert

View of the opened space between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments by Roger Robert

View of the opened space between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments by Roger Robert

One of my numerous publications on pudendal neuralgia

Special Thanks

Many people’s hard work and knowledge led to the development of transgluteal pudendal decompression surgery, the way I perform this procedure today. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Professor Roger Robert, Professor Oskar Aszman, Dr. Jamie Balducci, Dr. Jacek Bendek, Dr. Mario Castellanos, Dr. May Nour, Cindy Love, and many others.

I want to say a big thank you on behalf of my patients, whom I was able to help with the pain.

Pudendal Neuralgia and Associated Conditions

Here are some of the associated conditions with pudendal neuralgia you should be aware of:

1. Piriformis Syndrome

Piriformis syndrome is a neuromuscular disorder in which the piriformis muscle, located in the buttock region, compresses or irritates the sciatic nerve. This condition may coexist or be confused with pudendal neuralgia, as the pudendal nerve and sciatic nerve are in close proximity anatomically.

Patients with piriformis syndrome often present with pain, tingling, or numbness along the distribution of the sciatic nerve, typically affecting the buttocks and extending down the leg. Treatment usually focuses on addressing the underlying muscle tightness or dysfunction through physical therapy, stretching exercises, anti-inflammatory medications, and, in refractory cases, injections or surgery.

2. Interstitial Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis (IC), also known as bladder pain syndrome, is a chronic, painful bladder condition characterized by pain and pressure in the bladder area, along with a frequent urge to urinate. The pain associated with IC can be debilitating and can significantly impact the quality of life.

Pudendal neuralgia might be connected to interstitial cystitis due to the proximity of the pudendal nerve to the bladder and pelvic floor muscles, which influences the bladder’s sensation and function. Management of interstitial cystitis often involves multimodal strategies, including dietary modifications, physical therapy, medications to reduce bladder pain and inflammation, and sometimes surgical interventions.

3. Vulvodynia

Vulvodynia is a chronic pain condition affecting the vulvar area in women and is often described as burning, stinging, itching, or rawness. The symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and vulvodynia can sometimes be the same. This is because the pudendal nerve supplies feeling to the vulvar area.

There are many things that can cause vulvodynia, including hormonal, genetic, and inflammatory factors. It can be hard to treat. Treatment strategies are typically multimodal, including topical medications, oral pain relievers, pelvic floor physical therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and, in some cases, surgery to decompress the pudendal nerve.

4. Prostatitis

Prostatitis refers to the inflammation or infection of the prostate gland, predominantly seen in men, and is characterized by discomfort, pain, urinary tract symptoms, and sexual dysfunction. Pudendal neuralgia might be interrelated with prostatitis due to the anatomical pathways of the pudendal nerve in proximity to the prostate gland, impacting sensation and pain in the region.

Prostatitis can be caused by bacteria or something else. Depending on the cause, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, alpha-blockers, and physical therapy for the pelvic floor may help ease the symptoms.

Even though these conditions are different, they may share some symptoms, pathophysiology, and anatomical links with pudendal neuralgia, which makes diagnosis and treatment more difficult. A comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to evaluating and treating these conditions is crucial for addressing the intricate and multifaceted nature of pelvic pain syndromes.

Pelvic Pain Frequently Asked Questions:

Here are some frequently asked questions that may help you greatly:

-

What is Pelvic Pain?

Pelvic pain in women is a common symptom that accounts for up to 30% of visits to a gynecologist, yet it is thought that close to 70% of cases of pelvic pain are not of a gynecological origin. Chronic pelvic pain is defined as pain that has been present for six months or longer, is localized to the pelvis, and is severe enough to cause functional disability requiring treatment. It is estimated that chronic pelvic pain affects 15% of women in the United States sometime during their lifetime.

Yet, almost 60% of those patients do not have a proper diagnosis (and therefore no treatment). This is because this pain usually spans more than one specialty, and treatment requires physicians specifically trained in chronic pelvic pain. Those statistics are even more staggering because over 20% of women with pelvic pain miss work, close to 50% feel depressed, and in 90% of women, it affects their sexual life.

Pain during or a complete inability to have intercourse significantly affects personal relations between the patient and her partner and further adds to suffering. Despite the fact that chronic pelvic pain in women is more common than coronary artery disease, asthma, or migraine headaches, very few physicians specialize in its treatment.

Pain is often blamed on psychological issues, and patients are often referred to a mental health provider instead of getting treatment for their true, existing disease.

-

What Conditions Cause Pelvic Pain?

Multiple conditions may cause pelvic pain, often coexisting in one patient. Some of the more common conditions are:

- Endometriosis

- Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Spastic pelvic floor syndrome

- Adhesions in the pelvis and abdomen

- Pelvic congestion syndrome

- Pelvic nerve neuralgias

- Pain caused by pelvic mesh

The Arizona Center for Chronic Pelvic Pain offers comprehensive treatment for those and many other conditions causing pelvic pain.

-

What is Pudendal Neuralgia?

Pudendal neuralgia is a relatively unknown cause of severe pelvic pain.

In my practice, I define it as pain located in the area of innervation of the pudendal nerve. Pudendal nerve entrapment is an impingement of the pudendal nerve due to scar tissue, surgical supplies, or mesh.

Therefore, pudendal nerve entrapment is one cause of pudendal neuralgia. However, other causes, such as inflammation, spasms of the surrounding muscles, or other nerve diseases, may also cause pain.

-

What is Pudendal Neuralgia for Men?

Pudendal neuralgia is defined as pain in the area of innervation of the pudendal nerve. In men, the areas affected can be the penis, scrotum, perineum, and rectum. Pudendal nerve entrapment is described as compression of the pudendal nerve from ligaments, scar tissue, or surgical materials, which leads to pudendal neuralgia.

Some patients with pudendal nerve entrapment experience burning pain, but others may have a sensation of numbness. It may be present on one or both sides, and some patients experience problems with erection and pain with ejaculation. Penile numbness is one of the more frequent signs of pudendal neuralgia in men.

Conclusion

Managing Pudendal Neuralgia through transgluteal nerve decompression surgery can be a significant step towards reclaiming your life from chronic pain. By understanding the pre- and post-surgery expectations, you can better prepare for a smooth recovery journey.

Remember, the dedicated team led by Dr. Hibner is committed to supporting you every step of the way, ensuring that you receive the highest quality care and personalized treatment. Your path to relief and improved quality of life starts here.